The use of impact evaluation in local jobs and skills initiatives – The paradigm of the Vantaa GSIP Project

Introduction

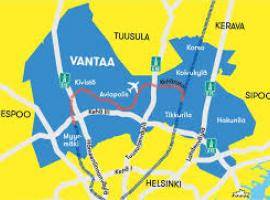

As discussed in the Journal No.1 of the GSIP (Growth and Social Investments Pacts) Project (https://www.uia-initiative.eu/en/news/gsip-expert-journal-1-get-know-project-and-what-happened-first-6-months), the GSIP Project reflects the City of Vantaa key policy decision: i. to promote growth and competitiveness of local companies; and ii. to improve level of education of workforce and offer better training possibilities for low-skilled employees, employees with outdated skills and unemployed persons, through the design and implementation of a new, innovative and exceptional service and incentive model (Growth and Social Investments Pacts - GSIPs). The GSIPs are tailored for Vantaa based companies employing 10-200 people, particularly companies involved in human intensive and routinely operated industrial sectors and IT-companies which have workforce of outdated skills caused by rapid changes in technologies and future business. They focused on three interrelated policy priorities: a) Recruitment of unemployed persons with low skills and education – The GSIP model No. 1; b) Training of existing staff – The GSIP model No. 2; c) Use of digitalization processes in the business routine – The GSIP model No. 3.

The GSIP Project has adopted a comprehensive monitoring and evaluation mechanism (M&E) comprising of three complementary components:

a) Self-evaluation and analysis conducted by the Project Management Team (https://uia-initiative.eu/en/news/management-and-monitoring-models-local-jobs-and-skills-initiatives-lessons-vantaa-gsip-project)

b) An external ex-post evaluation process, with the aim to analyse the implementation of the Project using four pre-defined criteria (relevance, effectiveness, efficiency and impacts) as well as to support recommendations for continuity, replicability and the scalability of the Project’s results and findings

c) An internal impact evaluation process carried out by the two independent research partners of the GSIP Project, the Research Institute of the Finnish Economy “ETLA” and the Labour Institute for Economic Research PT (https://uia-initiative.eu/en/news/how-could-independent-research-organizations-contribute-development-local-jobs-and-skills).

It is now time to discuss the context of the impact evaluation process and highlight its key results. This process differs from the other evaluation activities in that it utilized a randomized control design to overcome potential issues present if the participants were chosen merely based on their willingness to participate in various Project activities.

1. The context of impact evaluation

Impact evaluation is an assessment of how a specific intervention (a small project, a large programme, a collection of activities, or a policy) being evaluated affects outcomes, whether these effects are intended or unintended. A properly designed impact evaluation can answer the question of whether the intervention is working or not, and hence assist in decisions about scaling up. However, care must be taken about generalizing from a specific context.

A well-designed impact evaluation can also answer questions about design: which bits work and which bits don’t, and so provide policy-relevant information for redesign and the design of future programs. Policy makers, practitioners, stakeholders and beneficiaries want to know why and how a specific intervention works, not just if it does (G. Peersman, Impact evaluation, Better Evaluation, 2015, http://www.betterevaluation.org/themes/impact_evaluation).

It is not feasible to conduct impact evaluations for all interventions. The need is to build a strong evidence base for all sectors in a variety of contexts to provide guidance for policy makers. The following are examples of the types of intervention when impact evaluation would be useful: a) innovative schemes; b) pilot programmes which are due to be substantially scaled up; c) interventions for which there is scant solid evidence of impact in the given context and d) a selection of other interventions across an agency’s portfolio on an occasional basis.

Quantifying and explaining the effects of interventions is at the heart of the evaluation of local jobs and skills initiatives (https://ec.europa.eu/info/eu-regional-and-urban-development/topics/cities-and-urban-development/priority-themes-eu-cities/jobs-and-skills-local-economy_en). For local policy makers and practitioners to make informed decisions, it is important to understand what works or what does not, as well as why, for whom and in which contexts. This is a formidable list of questions, and the available analytical methods provide at best tentative and incomplete answers to most of them. It is, therefore, of fundamental importance to clarify which methods can answer which questions, under which circumstances.

Two conceptually distinct sets of questions tend to emerge when it comes to assessing the results of local jobs and skills initiatives: the counterfactual (outputs and outcomes in the absence of the intervention) impact evaluation (CIE) deals primarily with the quantification of effects; the theory-based impact evaluation (TBIE) concerns their explanation (European Commission, EVALSED Sourcebook - Method and Techniques, 2013, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/evaluations-guidance-documents/2013/evalsed-the-resource-for-the-evaluation-of-socio-economic-development-sourcebook-method-and-techniques).

a) The central question of CIE is rather narrow (how much difference does a treatment make?) and produces answers that are typically numbers, or more often differences, to which it is plausible to give a causal interpretation based on empirical evidence and some research assumptions. Is the difference observed in the outcome after the implementation of the intervention caused by the intervention itself, or by something else? Answering this question in a credible way is nevertheless a very challenging task. The CIE approach to evaluation is useful for many policy decisions, because: i) it gives easily interpretable information; ii) it is an essential ingredient for cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness calculations; iii) it can be broken down into separate numbers for subgroups, provided that the subgroups are defined in advance.

b) TBIE is an approach in which attention is paid to theories of policy makers, programme managers or other stakeholders, i.e., collections of assumptions, and hypotheses - empirically testable - that are logically linked together. These theories can express an intervention logic of a policy: policy actions, by allocating (spending) certain financial resources (the inputs) aim to produce planned outputs through which intended results in terms of people’s well-being and progress are expected to be achieved. The actual results will depend both on policy effectiveness and on other factors affecting results, including the context. An essential element of policy effectiveness is the mechanisms that make the intervention work. Mechanisms are not the input-output-result chain, the logic model or statistical equations. They concern beliefs, desires, cognitions and other decision making processes that influence behavioural choices and actions.

TBIEs do not focus on estimating quantitatively how much of the result is due to the intervention like counterfactual evaluations. Through different methods (such as "contribution analysis" or "general elimination methodology") they assess the plausible contribution of an intervention to observed changes. They can also incorporate counterfactual tools to test whether the result can be attributed to the intervention but will also use observational and analytical methods to explain the mechanisms leading to this result and the influence of the context.

2. The impact evaluation process of the Vantaa Project

Etla and Labore adopted and applied the CIE method during the project implementation period to provide solid information about the impacts produced by the intervention by comparing GSIP participants (Vantaa based companies employing 10-200 people, particularly companies involved in human intensive and routinely operated industrial sectors and IT-companies which have workforce of outdated skills caused by rapid changes in technologies and future business) to a randomly assigned control group. In practice, companies were randomly divided into two groups: the treatment and control groups. Only the companies in the treatment group were offered the service and incentive models. Due to the randomization, treatment and control groups were on average similar, and thus, comparing the changes in the mean outcomes of the groups, provided reliable information on how well the developed models work. Both extensive administrative data and multi-round survey data were used in the analysis.

Evaluators identified two areas of concern for their work. The first was to define precise outcome project indicators and to determine how to measure them. There are several challenges in finding relevant measures and data that captures the project targets. One of the main obstacles is the time frame of the impact evaluation. The project period (2018-2022), including creating and testing new ways to advance the local economy in Vantaa, as well as evaluating the effects of the developed solutions, is only a little more than three and half years (including an extension period given for some activities of the Project). The most reliable and extensive datasets can take a long time, even years, to be made available for researchers. Thus, it is difficult to find reliable data that capture the potential effects of the Project, especially those accomplished at later stages of the Project. In this context, evaluators utilized several different data sources to balance out the weaknesses and strengths of various data.

The second area of concern was that companies adopt in principle long-term strategies for their employment and production choices, and they do not alter these decisions lightly. Therefore, evaluators decided to include outcome indicators that attempt to capture early indications of any changes, such as improvements of information or attitudes of companies towards increasing the skills and competences of their employees or adopting new technologies.

The impact evaluation utilized a randomized control trial methodology. This approach imposes some important requirements for the collected data and subsequent analysis. In particular, it is essential that the data covers companies (and employees) in both the treatment and control groups. Main data sources were administrative register and survey data (the first survey round was conducted in the spring 2019, before the treatment firms were approached and before they were offered any service and incentive models; the last two rounds of the survey took place in October 2020 and 2021), as well as company databases for contact information.

Firms were divided into six clusters based on their main industry (three clusters) and on the number of their employees (splitting all three clusters in half). Evaluators randomly assigned half of the firms in each cluster to the treatment and control groups. The firms in the treatment group (and their employees) received the Project services, whereas the firms (and their employees) in the control group were not.

3. The results of the impact evaluation process

(a) The quantitative targets set for participation of the key beneficiaries (local companies) were clearly achieved. 65 companies took advantage of the Project services, which surpass the goal set in the Project Plan by 8 percent. A large share of the participating companies was involved in more than one Growth Pact (https://uia-initiative.eu/en/news/gsip-project-story-during-2021-journal-3), indicating high level of satisfaction among the treated companies. Growing firms and firms that were making also other investments simultaneously were more likely to participate in the Project services.

(b) The quantitative targets set for each Growth Pact were hardly achieved due to a variety of external factors strongly connected to the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on the Vantaa labour market. In addition, the impact evaluation confirmed that companies still follow long-term strategies in terms of productivity and use of human resources, which are not eager to change drastically. Achieving changes in these fundamentals is a challenging and a long process.

(c) Due to these challenges, it is believed that the businesses and the Vantaa area may have experienced improvements, not firmly validated by the impact evaluation process. A major lesson for any future local jobs and skills initiative must be to take into account also the requirements of an impact evaluation when planning the project. This is the only way to increase understanding of what delivers and how (H. Karhunen and H. Virtanen, Impact Evaluation in the Urban Growth Vantaa Project, October 2022, https://uia-initiative.eu/en/news/impact-evaluation-urban-growth-vantaa-project).

4. Key conclusions

Etla and Labore, the two independent research partners of the GSIP Project, applied the CIE method to provide solid information about the impacts produced by the intervention - positive and negative, intended and unintended, direct and indirect. They also identified key strengths and limitation of the approach that should be taken into account by local policy makers and practitioners across Europe.

Despite its wide applicability, the CIE method is not the magic bullet of impact evaluation some claim it to be. On its positive side is the fact of not requiring complex data structures to be estimated, just aggregate data on policy outcomes, collected before and after the intervention. As one applies the method in practice, its limitations start to become clear.

On the practical side, the need of pre-intervention outcome data often represents an insurmountable obstacle, most often because of lack of planning in data collection. On the more conceptual side, the simplicity of the method comes at a price in terms of assumptions: the crucial identifying assumption to obtain impact estimates is that the counterfactual trend is the same for treated and non-treated units. This assumption can only be tested (and relaxed if violated), if more data are available.

In this context, interested authorities should discuss the possibility to apply more integrated concepts of impact evaluation processes during the design and implementation of innovative local jobs and skills agendas, which may combine both CIE and TBIE methods. Like any other evaluation, an integrated impact evaluation should be planned formally before the adoption of an initiative and managed as a discrete activity with the following phases:

- Describing what needs to be evaluated and developing the evaluation brief;

- Identifying and mobilizing resources;

- Deciding who will conduct the evaluation and engaging the evaluator(s);

- Deciding and managing the process for developing the evaluation methodology;

- Managing development of the evaluation work plan;

- Managing implementation of the work plan including development of reports;

- Disseminating the report(s) and supporting use.