Ravenna Mapping Darsena: In search of visions, lost and found

The transformation of Ravenna’s Darsena area has been on the city’s agenda for decades. However, most efforts to regenerate the neighbourhoods along the Candiano Canal, the waterway leading from the city centre to the Adriatic sea, have been focusing on improving the architectural aspects of this district through architectural competitions and grandiose development plans. While most of these schemes failed to bring about the desired impact on the territory, the project DARE started from very different assumptions.

The most important riches of a territory, before its economic assets, urbanistic features and architectural values, are its people: residents who inhabit an area or those who work, spend their leisure time and bring their ideas there. For a development project to cater for the inhabitants and users of an area, it is not enough to match their expectations but to build on the ideas, visions, narratives that are already there.

If physical sustainability lies in the reuse of existing buildings, spaces and materials by reformulating them to create a continuity in the urban form, social sustainability builds on a convergence of hopes, efforts and imagination related to the transformation of an area. This is why DARE begins with a careful exploration of practices, projects and policies that exist in the territory and that help identify the main themes, ideas and concerns that the Ravennati have projected onto Darsena, and that serve as a basis for the urban regeneration of the area. This information adds to the data collection process that is at the core of DARE: by building a new knowledge infrastructure and digital environment around Darsena, the project will explore features and trends in the district’s evolution and will share them among decision-makers, local businesses, residents and active communities around Darsena. “Data can have plenty of formats and sources and their collection is not just a digital matter,” reminds me Emanuela Medeghini, project manager of DARE.

The task of mapping initiatives in Darsena is carried out by Multilab, a temporary association of enterprises led by KCity and composed by Nomisma, Labsus and Politecnica. KCity is a Milan-based company with a decade-long history in managing and designing urban regeneration processes. It has been working on regeneration projects across Italy, mainly with public administrations and third sector entities, but with an increasing interest by private property owners. The organisation tends to deal with urban voids, meaning “spaces, be they abandoned, disused or underused, with chances to be reused if we can build reuse strategies or imagine for them new forms of uses,” explained to me KCity’s project manager Dario Domante during an online interview organised to discuss the methodology behind the mapping process.

The analysis conducted by Multilab in this first phase of the DARE project is based on a methodology developed by KCity through a series of experiences in other territorial contexts and is rooted in the concept of strategic incrementalism. This concept refers to an idea of urban transformation done gradually, with successive steps anchored to a long-term strategy that directs these steps while also being shaped by them. Strategic incrementalism goes beyond the concept of “temporary use” that has become very popular in European cities in the 2010s. “We don't really like to talk about temporariness, we rather talk about transience, imagining that the same activities that define the initial steps of a reuse process can also inform the long-term strategy,” underlines Domante. According to this incremental approach, the contribution of local stakeholders is decisive and fundamental: the process begins with an analysis of the territory that helps in identifying development potentials and tries to leverage local resources and energies in order to set the first steps of the urban regeneration strategy.

Map of policies. Image (c) MultiLab

The mapping methodology developed by KCity follows a process that includes a variety of research layers. Mapping begins with a desk analysis, an online consultation of websites, newspapers and other media, development plans of the local administrations and public-civic collaboration agreements in the area. The information collected from the desk analysis allows the consortium to frame the elements that characterize the territory. To complement the desktop analysis, researchers also look for informal practices that can only be collected by direct observation. Domante gives an example: “we take a walk and explore the area to find informal activities like fishermen who habitually go to the Candiano Canal to fish.”

The analysis continues with interviews: researchers exchange with a series of people who are active in the area and carry out initiatives locally. “We realised a mapping of actors who have, over time, presented projects for Darsena,” explains Ottavia Starace, another member of the KCity team who works in DARE. Information based on the interviews enables the researchers to establish the broader cognitive framework in which to position the individual activities explored. The first step is to understand what happens in the area and what kind of relationships are established between these initiatives and the surrounding space. “We try to understand what are the themes dealt with specifically by the initiatives, as the goal of mapping is to try and transform these practices into themes that can be useful for the design activity that will follow,” clarifies Domante. The mapping of initiatives, past and present, includes the exploration of economic and human resources that enable these initiatives to be transformed into concrete actions.

The next step of the analysis is to categorise all the data in macro-themes: practices, projects and policies. In this categorisation, practices refer to concrete (formal and informal) uses and reuses (events, meetings, care actions, social animation activities and various forms of using the urban space) taking place in the area. Projects, in turn, are ideas and project proposals that have emerged over time for the reuse and enhancement of the district (e.g. action plans, theses, project proposals, etc..), not necessarily linked to formal development strategies defined for the neighbourhood by the competent bodies. Lastly, policies refer to strategies, sectoral regulations and development schemes included in the municipal plans or strategic guidelines adopted by the local administrations.

The last step of this preliminary research is to look for the commonalities among the various activities mapped in the territory. ”Thanks to this mapping we have identified a number of recurring themes, including art and culture, work and economy, hospitality and living, sociability and proximity, sport and physical activities, environmental sustainability, water and infrastructure,” concludes Starace. This division in macro-themes also permits to associate stakeholders with each other in order to stimulate networking and partnership in the regeneration process of the area.

Mapping the practices, projects and policies developed in and for the area allows the DARE consortium to detect the interests that Darsena has attracted and the expectations that its protagonists have raised. This mapping goes beyond the present state of affairs in the area: extended to the past decades, the mapping process includes initiatives “that are no longer current, but which at least lead us to questions to which some practices in the area have tried to construct answers,” justifies Domante.

For a better overview of the findings, the practices, projects and policies identified during the research have been placed on a series of maps, together with their initiators and other key subjects in the area. Besides these maps, the practices, projects and policies identified throughout the analysis have also been visualised in a set of diagrams, helping to comprehend better the nature of these initiatives and recognise the connections between them. Such a perspective offers a comprehensive overview of Darsena area: it allows users to see all the selected elements at their geographical locations, filtered through the different layers of categories and macro-themes, with the objective of “understanding what the key issues of the area are and at the same time understanding what local actors are present,” explains Domante.

Diagram of projects. Image (c) MultiLab

These findings were shared during a workshop in November 2020 where partners of the DARE consortium were invited to reflect together on the results of the mapping process and add their own references to the map, indicating if some key practices, projects, policies or actors are missing from the collection. To help joint work, the practices, projects and policies identified during this research have also been georeferenced and simply placed onto Google’s MyMaps platform with an information sheet linked to each of them, allowing other partners of the DARE consortium to work with this data and develop their own interpretations.

Reflections on the categorisation of practices, projects and policies raised the issue of transversality. As Medeghini pointed out, “categorisation is a useful trick to seize complexity and conceive the big picture. But as our trajectory goes towards integration, multi-purpose projects and long-term processes based on cross-sectoral collaboration, we have to be careful not to be trapped in categories.”

The insights of consortium partners led to an agreement that some of the themes initially identified as independent, like environment and sustainability or water and infrastructure, are actually transversal to the development strategies that are implemented in the area: “most practices that focus on the themes of sociability or green spaces, environmental sustainability, do also integrate the themes of culture and arts, as well as the reuse of spaces to generate proximity services,” concluded Medeghini.

Supported by a scenario analysis conducted by DARE partner Nomisma, based on demographic and economic data, the goal of this process is to transform the mapping of the territory into planning perspectives and turn the key issues into possible planning directions for the regeneration of the area. Based on the refined set of macro-themes (art and culture, work and economy, hospitality and living, sociability and proximity, sport and physical activities) and transversal themes (environmental sustainability, water and connections), KCity has developed three design thrusts or guidelines that Domante describes as “guiding ideas for building the tactics for the urban regeneration of the neighbourhood.” These speculative guidelines – Darsena Laboratory (for innovative solutions based on current trends), Multifunctional Darsena (for a functionally integrated neighbourhood around Darsena) and Adaptive Darsena (for services responding to the Covid crisis) – serve as a basis for future-oriented critical reflections.

In the next phase of the project, these guidelines are refined during a co-planning operation with local actors, selected through a second stakeholder mapping process. This mapping process is based on a participatory methodology that aims to identify local stakeholders with whom to try and build a relationship aimed at defining collaborative projects. During this phase, a dialogue is organised with key local actors of the projects that have been mapped. The main goal of this phase is to define, based on all the themes previously identified, three tactics with an integrated value that could affect the territory and fit the community’s needs while being, as Domante envisions, “capable of maximising the contribution of the territory’s resources.”

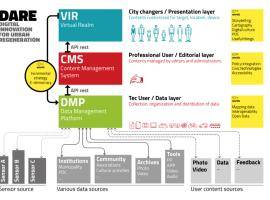

The guidelines will be cross-checked with a variety of data and information collected from different sources and treated within the DARE digital platform; such data will also serve at a later stage to assess the impact of projects on the local environment. The DARE project has designed a road-map including the identification of more possible tactical approaches and themes and an open call for project ideas. Based on the reactions of the stakeholders and community members, such “themes” will become possible “tactics,” or sets of integrated projects. Citizens will be called to select their preferred tactic with the help of an e-democracy exercise. In these phases, the role of the municipality, supported by the consortium’s Process organiserS Team (POST), will be to guide and support organisations and citizens in developing collaborative projects. Later on, the “winning” tactic will be elaborated further, with the help of various expertise, towards its implementation.

In contrast with previous attempts to revitalise Darsena, these initiatives will not necessarily translate into architectural forms. Despite its long duration and broad outreach, the results of this process are not carved in stone and its design lines are not immutable. As Medeghini reminds me during an online coordination meeting, the mapping operation and the development of proposals will “progressively intersect with the data collection and sharing operation, and the themes will be further developed in the light of new data assembled also with the help of the future digital platform” that DARE’s developing.

For this is the essence of the incremental model: reanimating Darsena’s imagination, based on mapping practices, projects, policies, and bringing together local actors to develop proposals is but one of the several, mutually enriching threads of the DARE project. It is with a multitude of different actors and competences, that these threads are woven together in the project’s tissue, constituting a more complex vision of Darsena, connected with the neighbourhood’s needs and aspirations through many strings.