Process and overview

UIA established seven challenges related to the implementation of innovation projects. These apply across all 86 UIA projects, providing a consistent framework against which we can track each project’s journey.

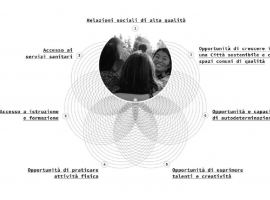

This innovation challenge matrix has provided the structure for two workshops held with WISH-MI partners to date. The first of these was held in May 2022, with the scores shared in Journal 1. The second was held in May 2023. In each case, the process consisted of a participative session joined by all project partners. Using sticky notes, participants were invited to score the WISH-MI project against each of the innovation challenges on a scale of 0-5 where 5 is the highest score. These were placed on a wall-mounted matrix and once all the content had been posted, there was an extensive moderated discussion on the scoring, to understand why partners had given their scores, and to find an aggregate figure for each of the challenges.

A photograph of the eventual chart is shown below

The image shows that there was consensus in some areas and disparity in others. Specifically, the scoring ranged as follows:

- Leadership: 0 to 3

- Public Procurement: 1 to 3

- Cross-departmental working: 1 to 4

- Participative approach: 2 to 5

- Monitoring and Evaluation: 2 to 4

- Communication with target beneficiaries and users: 1 to 4

- Upscaling: 1 to 4

Based on the data inputs, an average score was produced for each challenge, using the same approach used in May 2022. The resulting scores from both sessions can be seen in the figure below.

Source: Expert’s data from WISH-MI Partner workshops

In terms of headlines, this image shows that in two of the challenge areas (Public procurement and Communication with target beneficiaries) the scores remained the same. In another two domains (The Participative Approach and Monitoring and Evaluation) partners felt that there had been some improvement. In the remaining three challenge areas (Leadership, Cross-departmental work and Upscaling) partners felt less positive than they had done one year ago.

Further details, and some interpretation on the scoring, is set out below.

1. Leadership

Feedback on the leadership challenge indicated an absence of senior leadership championing the project since the departure of the initial project lead in the spring of 2021. Non-municipal partners stressed the valuable day to day leadership coming from the City of Milan team, and the effort they have made to sustain the project. However, it was at the strategic level that a leadership vacuum was identified, resulting in a short-termism and hand to mouth culture which had limited the project’s implementation - and potential sustainability.

In practice, other partners - such as the Catholic University of Milan, which hosts the Children and Young People’s Guarantor - have assumed a proactive role, helping to drive aspects of the project such as the Teen-Voice Milano project and the efforts around building transnational connections.

Expert’s comment:

A number of factors help explain the rather low scores around leadership. First, it’s important to note that the project was initially led by a highly capable senior staff member with strategic vision and a strong commitment to the project. His departure, without direct replacement, has left a gap that the project has not managed to fill. This absence of a vocal champion within the city’s senior management team has doubtless affected the project - and the partnership experience.

A number of significant external factors - most notably COVID and the Ukrainian refugee crisis - have also been significant, in terms of stretching human resources and distracting the attention of other key municipal managers beyond the project. However, it is still important to note that senior managers within both the Education, Welfare and Health departments have collaborated effectively - and continue to do so - encouraged by the WISH-MI structure. This is reflected in partners’ positive comments around the day to day management of the project.

2. Public Procurement

The scores for this challenge remained the same in both workshops, at an average of 3. Partners are largely resigned to a slow bureaucratic procedure that is hard to turn around. However, key lessons have been learned through the WISH-MI experience and the experimentation with the collective vouchers has generated some optimism around ways to fund the co-design and delivery of new services in different ways.

Expert’s comment:

The WISH-MI experience under this challenge has bumped into a question often raised in public innovation circles. How can we attract innovative service providers, often unfamiliar - or reluctant to engage with - the public procurement system, and deter low quality providers who win contracts through their knowledge of how the system works?

WISH-MI has thrown up some key lessons. For example, it is insufficient to post a call on the municipal website and expect a flood of innovative proposals. Reaching new innovative providers requires a strong communication effort, aligned to a proactive approach to nurturing new relationships. Alongside this, continually looking to simplify and streamline procedures is helpful in demystifying the procurement experience, especially for new and smaller suppliers.

Although the design and implementation of the voucher system has been challenging, it offers potential opportunities in a number of respects. Most obviously, it can help reach marginalized young people and families, through incentives. But it has also created a mechanism that can encourage dialogue between service commissioners and providers as well as supporting a co-design process with service users. In the context of Milan this is an exciting breakthrough with real potential.

3. Cross-departmental Work

This is one of the challenge areas where the partnership score has decreased since May 2022. In the workshop session, partners from outside the municipality were quick to applaud the efforts made by those most directly involved in the project. But there was a clear view that this cross-departmental collaboration was largely confined to the middle management and officer functions, but not reflected in the higher echelons of the city administration.

There was also a strong sense that communication across departments - and indeed across the city- related to the project, could have been more effective, which might have supported work across the various departmental silos.

Expert’s comment:

Given WISH-MI’s focus on aligning policy interventions under a single aligned wellbeing banner, this feedback is disappointing. It was also somewhat unexpected, after the positive comments generated in the initial session one year ago. What is behind this change of opinion?

In the intervening year, the commitment to tackle this challenge has been diluted through lack of capacity and the absence of strong strategic leadership within the project. At the outset, with the initial leadership model in place, there were high levels of optimism about the possibilities ahead. Although the collaborative engine room at the middle-management level remains in place, it has been severely stretched due to resource issues.

However, while this is true, it is also possible that external partners do not fully appreciate the significance of the progress made within the city administration by the production of an integrated strategic plan that informs the work of several departments. This marks a step change in addressing silo-based activity.

The low external visibility on these developments, subtle but potentially important, has been exacerbated by the fact that internal developments within the administration have perhaps not been sufficient promotion within the wider partnership. For example, the campaign to recruit and train 100 0.18 ambassadors across all municipal departments is potentially game-changing but has been quite low key to date in its communications.

4. The participative approach

The participative approach is one of the challenge areas where we can see a higher score in May 2023. One year ago, partners remained in a post-COVID situation where outreach activity had been stymied and there were significant obstacles to delivering participatory approaches.

Now the picture looks different. Through a diffuse range of activities WISH-MI is now supporting a number of different ways to promote higher levels of participation with service providers and end-users.

On the key question of participation with young people, the Teen-Voice Milano activities led by the Catholic University of Milan, are an innovative development. Partly inspired by the relationship WISH-MI has built with other cities (in particular, Vienna) the University has recruited a group of young people to provide a voice on behalf of the city’s young people. This is currently focused on adolescents, who are often more difficult to engage. An important milestone for this took place on 26th May when the group had an official meeting with senior politicians in the city.

Alongside this, the full roll-out of the hubs - described earlier in this journal - has provided an opportunity for young people to shape the services offered on their doorsteps. Another important step, not only in terms of widening the dialogue, but also promoting the visibility of the WISH-MI initiative in the priority neighbourhoods.

The invitation to service providers to co-design new provision supported by the collective voucher model has also provided a different kind of participative avenue. As a process, this remains in its infancy, and there are questions about the extent of youth intervention in the design of these services. However, it is there in different shapes and forms and with continued support and encouragement it can further develop.,

Expert’s comment:

The increase in scores here is probably due to the fact that in May 2022 not all partners had insight into the pipeline of planned activities - or were perhaps sceptical that these would emerge. Such developments take time, but in retrospect there may be important lessons about keeping all of the partners on board to at least a minimum level.

The changes triggered by the collective vouchers are interesting and encouraging. However, they represent the vanguard of a culture shift that cannot take place overnight and that will need much reinforcement and support if it is to bed in. It may also need some level of capacity building, and measures to showcase and share good practice, as a source of inspiration to the city’s service providers,

5. Monitoring and Evaluation

Monitoring and Evaluation received one of the lowest scores in May 2022. At that point, there was no detailed monitoring and evaluation framework and no tangible procurement process under way to appoint external evaluators.

The achievement of these tasks, undertaken in late 2022 and early 2023, is due to the considerable efforts of the officers within the WISH-MI team who prepared and managed the contractual procedures. Consequently, a team is now in place, working to a clear framework set out in the call for tenders.

Expert’s comment:

A variety of factors - all previously mentioned - conspired to prevent the Monitoring and Evaluation contract being let until spring 2023. This is far from ideal, as it means the appointed team comes in just at the point where the project is starting to focus on its final stages. A cumulative evaluation, running concurrently with the project, would have been more effective, however it is still good to see that arrangements are now in place.

One of the challenges to any Monitoring and Evaluation approach is the ambitious scope and scale of WISH-MI. The city has adopted a pragmatic approach to this, by confining the M&E work to specific aspects of the project. Significantly, this will lack the longitudinal dimension required to demonstrate impact over time for the young beneficiaries. Once the evaluation report is completed we will revisit this, reviewing what has been produced and drawing key lessons from the overall experience.

6. Communication with beneficiaries

The challenge of communicating with target beneficiaries and users remains largely unresolved as WISH-MI enters its final phase. This is reflected in the consistently low scores generated by partners in both of these workshops. This challenge scored only 2 from 5, the lowest when we conflate the scores both sessions.

Partners acknowledge that the challenge is complex and difficult, given the profile of the target beneficiaries. They also accept that recent developments - most notably the launch of the microsite - have been too recent to fully evaluate at this point. However, consistent points were raised in the two workshop sessions, for example relating to the low profile on social media and communication channels used by children and young people.

Expert’s comment:

Overall, there had been an absence of a strong strategic approach to this challenge. The diversity of the target group - for example the different age cohorts - presents challenges, although these were understood from the start. And although this is not easy, other cities - most notably Vienna - have shown what can be achieved through the effective use of intermediaries and targeted messaging, complemented by good tools and capacity building support.

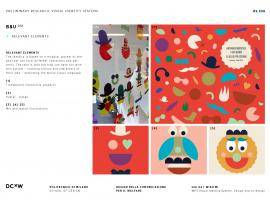

This does not decry the excellent work led by the Politecnico di Milano to create a shared visual identity for Milano 0.18. The team involved has adopted an innovative approach to this task, covered in an earlier article, and they have generated some creative and playful tools to involve children and young people. This includes a digital space where users can generate their own unique version of the Milano 0.18 logo.

7. Upscaling

Upscaling is another area where partner scores have dropped from 2022. The original idea was that WISH-MI would provide a sandpit for experimentation and for prototyping concepts that could be scaled up within the administration and across the city. There is now less confidence within the partnership that this will be the case.

In fact, the May 2023 workshop opened up concerns about the sustainability and viability of the WISH-MI ecosystem. Although several components are likely to continue, none of them are secured and the original expectations to upscale - for example across more neighbourhoods - seem unlikely to materialise at this point, and rests with senior decision makers.

On a more positive note, and indirectly related to upscaling, the WISH-MI concept has attracted the attention of other cities, tackling the same issues as Milan. So although the project has a questionable future - in its entirety - within the city, there are possibilities to cascade and transfer it - or parts of it - more widely.

Expert’s comment:

This final challenge reveals the interconnected nature of the seven challenges. None of them stand alone, and the root causes of the difficulties around upscaling, come back to difficulties identified elsewhere. The lack of a strong consistent leadership voice at the senior table is one. Related to that have been the difficulties embedding cross-departmental working at deeper levels. Without these, WISH-MI remains rather vulnerable. As upscaling often requires an innovation to have taken systemic root, it is not surprising to hear that this element is contested and unclear at this stage.