Lessons learned

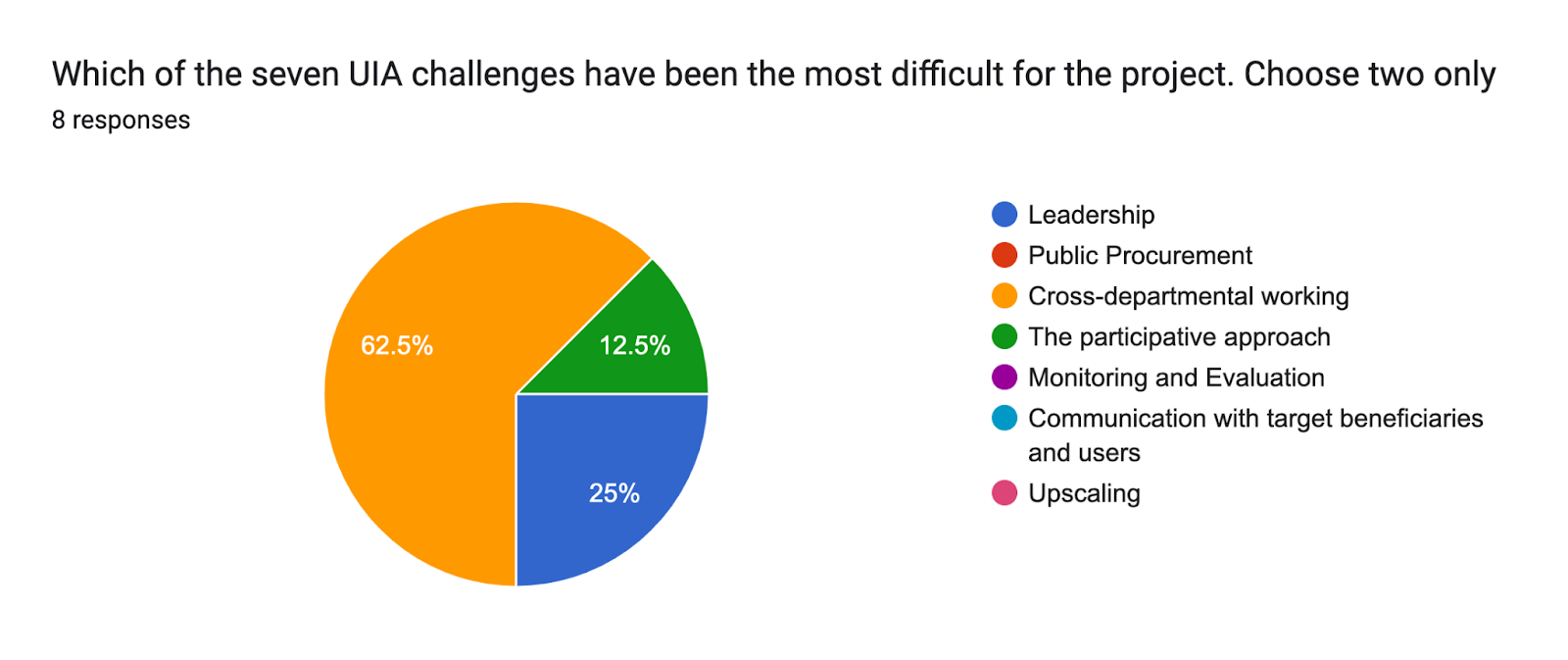

Throughout the project we have retained a focus on how WISH-MI has performed against the 7 UIA innovation challenges. From the partnership perspective, the top three that have caused the most difficulty have been broadly consistent, and these are shown in the figure below:

Source: WISH-MI Partner Survey, November 2023

These data provide a helpful starting point to our review of the key lessons from this innovation project. Shifting public-sector culture doesn’t happen overnight - and partners need to be kept in the picture.

We have already noted that WISH-MI has provided a catalyst for municipal reform within the city administration, evidenced through a new strategy, a changed approach to budgets and the introduction of mechanisms to present youth well-being as a cross-departmental responsibility.

However, the slowness and complexity of this aspect of WISH-MI has been a source of some frustration to partners, as evidenced in the survey results. Central to this, in terms of partnership working, is the importance of open and effective communication, so that everyone is kept in the loop. At times, largely due to staffing issues and operational pressures, external partners did not always feel fully up to date with developments, which has led to frustration and disappointment.

In the end, as we have seen, partners are on the whole optimistic about the direction of travel, even though progress has been slower than some had hoped for.

Visible operational leadership is essential

This point seems obvious. However, the frustration within the partnership was exacerbated by middle-management discontinuity within the City administration which led to periods of uncertainty and drift. The loss of the project leader at a relatively early state in the project was a key factor here. His partial replacement by a colleague who was already heavily committed on other duties, then had to assume a major city role in the Ukrainian refugee crisis, meant that the senior management input was stretched even more thinly. Although the day-to-day operational work was much appreciated, partners sensed (rightly or wrongly) that this diminished senior management input reflected WISH-MI becoming a lower priority in the scheme of other challenges.

The conclusion from this is the need to match the scale of your ambition with the appropriate staffing resources, particularly in relation to the operational leadership of the project.

Participative processes require careful design and ample time

The participative approach is the third challenge highlighted by partners as posing difficulties for the project. In fairness, the timing of the pandemic had a huge impact on this important aspect of WISH-MI. And although the project gained a time extension at the end, the original plan was for intensive activity during the initial months to engage young people and their families face to face in their communities. This did not happen, and by the time the crisis had passed, that key moment for the project had been lost.

Largely as a result of COVID, the project was playing catch up for the remainder of its lifetime. This had implications for WISH-MI’s commitment to the involvement of young people and their families in service co-design. For example, due to procurement timeline pressures, the scope to involve service-users in the design of potential new services to be supported via the voucher scheme, was limited.

The WISH-MI focus on child wellbeing provides a helpful entry point

Despite its implementation challenges, the WISH-MI experiment suggests that adopting child wellbeing as a focal point brings a number of benefits. From the public sector perspective, it creates a common denominator that cuts across departmental and organisational silos. This has encouraged collaboration across policy areas - for example education, health and culture - that are typically kept apart due to strict administrative and budgetary distinctions.

At the strategic level, the establishment of a cross-departmental steering group has committed senior officials to this collaborative process. The development of the 0-18 strategic plan, and the ongoing work on a shared governance model, have resulted from this high level commitment. At the operational level, initiatives like the 0-18 Ambassadors have created champions across the municipal structure and communicated the key message that child wellbeing is a universal responsibility.

Putting children at the centre is vital, but remains work in progress

Partly due to the impact of the pandemic, Milan’s aspiration to embed child participation at the heart of WISH-MI was not fully realised. The municipal culture and structures were at times too inflexible to meet the project’s ambitions, and despite the advances made (for example the cross-departmental Youth Ambassador model), much work remains to be done here. However, several WISH-MI partners did manage to experiment with new ways of working with young people through establishing mechanisms to engage them. Action Aid and ABCittà, organisations with deep participatory cultures, are among them whilst the Catholic University pioneered the Teen Voice initiative, which brought together a group of young people to advise the city’s Youth Guarantor.

Finally, through its interest in child-centred policy processes, Milan developed links with other cities - most notably Vienna - which provide scope for this area of work to evolve further.

Recommendations to other urban authorities who wish to implement similar innovative projects

Sadly, the scale of deprivation and exclusion experienced by a growing number of young people in Milan is not peculiar to that city. Nor are the service delivery challenges identified in the original WISH-MI application:

- Awareness of service provision

- Understanding of entitlement to services

- Traditional top-down public service offer

Consequently the WISH-MI innovation challenge and intervention logic remain legitimate, not only for Milan, but for many cities, especially larger metropolitan ones with fast changing populations.

Provided a city has the political will to address these issues then the overall WISH-MI concept may provide a useful framework. The fact that the concept is modular is an advantage, meaning that other cities can select aspects of the approach best suited to their own setting. Furthermore, although WISH-MI has been a complex and difficult journey, the city actors have gathered a wealth of skills and experience along the way, which are worth sharing with a wider audience.

In the final survey of WISH-MI partners, all of them saw the model as being transferable. Their feedback included some useful tips for other cities, which included the following:

|

“The aims of the project and the outcomes, even if partial, of the actions developed indicate that it is very appropriate for an administration to follow the path traced by the project. This logic of intervention with appropriate adjustments can truly become a model where local governments have real interest in working in a participatory and interdepartmental way for the welfare of citizens 0-18 years old.”

“What is needed is real political involvement, timely and effective communication of the project, a real willingness to listen to the community and citizens, especially children, and adolescents living in the most fragile areas. A long-term strategy is needed.”

|