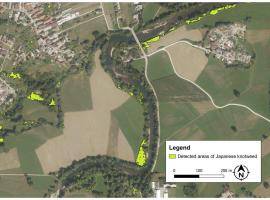

Research on wooden letters for letterpress printing in the USA

In the United States of America, however, wood type production was blossoming, and to this date, there are two commercial manufacturers still in business with full process recovered. Besides that, a little town Two Rivers (WI) was once the headquarter of America's biggest wood type factory, that later became Hamilton Wood Type and Printing Museum (HWTP). A massive collection of 1.5 million pieces of wood type makes it the world's biggest collection of its kind. A group of volunteers still keep a small scale production alive.

The purpose of my one-month stay in 2018 in the USA was threefold. Main goal was to visit all the three producers and actively learn the process. Based on the knowledge gained we intend to set up a similar workshop and start wood type production from invasive alien tree species Box elder (Acer negundo). Second purpose was to study relevant archives with a specific focus on wood type specimen books. In most cases they are difficult to find (sometimes only a few copies still exist). Studying the originals is important to understand design principals and details, which especially applies to chromatic wood type. The third goal?

Rochester (NY) was the first stop. Mrs. Gary McCormick from Virgin Wood Type and her late husband Bill inherited 100 crates of type patterns from American Wood Type Manufacturing Co. From the same company they bought a large custom made pantograph, one of the three machines essential for wood type production.

Their production starts with pre-ordered sweet maple planks that are first cut to smaller sizes, which are further, used as end-grain pieces. The face where a letter is going to be engraved is polished and treated with shellac to seal the grains. The slabs are now mounted on one side of pantograph. On the far side of the pantograph a pattern of a letter is fixed and both pieces have to be carefully registered.

.jpg)

Marko Drpić and Gery McCorrick from Virgin Wood Type

Pantograph has a few vital parts: electric power router, a tracer and a mechanical linkage in form of parallel rods that connects them. Moving a tracer along the borders of a pattern moves a router bit on a maple slab, reduced a few times, depending on the size of the letter being made. Tracing is done by hand and physically demanding due to the robustness of the pantograph. Once routed, the letter is cut to the right width on a trim-saw. Instead of an inch scale, this type of saws use typographic unit called pica (Didot point in Europe). Next step includes manual trimming of all the inner corners of a letter that are rounded due to the rotation of a router bit. Trimming is done with a sharp blade. A set of letters already trimmed is than proofed on a proof press. This helps to discover all possible mistakes: wood cracks, chipped-of parts, scratches, untrimmed areas.

Still in Rochester, Institute of Technology houses one of a kind collection of books, type specimens, manuscripts, documents, and artifacts related to the history of graphical communication, the Cary Graphic Arts Collection. During the visit I was focused on wood type specimens, mostly dated to the second half of the 19th century.

Second stop was Moore Wood Type in Columbus, Ohio. A small workshop is run by Mr. Scott Moore. His background in teaching all kind of production methods, from manual carpentry to robotics, enabled him to recover the process of wood type production to the finest detail. Although not traditionally done he first glues end-grain slabs in a bigger slab (approx. 30 x 30 cm) which makes milling much more efficient. Here I have learned how these slabs are thinned on a very special and rare machine called block leveler. This step is important as it provides good foundation for the next step — drum sanding, which bring slabs to the right thickness. This process needs 0.01 of a millimeter accuracy as wood type is often printed with metal type and the heights of both have to match. The routing was further done as described above, only on a table top pantograph.

The final step was HWTP in Two Rivers. During my visit the museum hosted around 250 designers, typographers and printing professionals from around the globe on an annual Waysgoose conference. Full demonstration of wood type production was given to the participants. There the original machinery and tools are still in use, with the exception of log trim saw and a huge block leveler which don't meet today's safety standards. Three days conference was an excellent opportunity to exchange information with the leading professional from the field.

Author of text and photographs: Marko Drpić, Founder of Studio tipoRenesansa