From proposing to collaborating and voting: participatory tools for the Darsena

How to use a participatory platform in the development of a new vision for a neighbourhood? The Urban Innovative Actions-funded project DARE made use of the e-democracy platform developed by BiPart at various phases of the project: from publishing their project ideas, to building synergies an voting for the best vision for Ravenna’s Darsena area, citizens were invited to familiarise themselves with digital tools in order to take part in local decision-making. In this article, UIA expert Levente Polyak met members of the organisation BiPart to explore the use of digital democracy tools in DARE.

Rising authoritarianism in national politics, and manipulative imitations of participatory processes led to a diminishing trust between power and public administrations on one hand and citizens and civil society organisations on the other, making many Europeans turn their back to democratic processes. Therefore, rethinking the methods, instruments and processes of democracy have never been more urgent than today.

In parallel with the polarisation of national politics, cities, towns and many rural municipalities across Europe witnessed a progressive turn: with experiments in participation and deliberation, they opened new ways for citizen participation as well as public-civic cooperation. It is not purely coincidental that local administrations have become more attentive to the expectations of citizens and civil society organisations: responding to daily needs and sometimes very practical challenges, local municipalities have often developed a more hands-on approach to public-civic exchange and cooperation with citizens.

In its quest to rethink Ravenna’s Darsena area based on inputs by citizens, the UIA-funded DARE project has been relying on the digital democracy tools of BiPart, a Milan-based organisation. During the project, I met several times with Stefano Stortone and Giulia Barbieri to discuss BiPart’s role in DARE and innovative uses of digital platforms for urban regeneration.

The first time I met Stefano and Giulia, we organised a meeting in a café in the centre of Ravenna. “I studied the crisis of democracy and I was really involved in how to solve this crisis,” explained Stefano. “I looked for methods to involve citizens in more structured ways, organising new processes, establishing new institutions to come up with decisions in a more collaborative way for urban areas.” Such methods for Stefano did not mean involving citizens in the classic forms of representative democracy but to develop new forms of governance with more engagement and more ownership on the side of citizens.

Stefano Stortone founded BiPart in 2016, borrowing the organisation’s name from Bilancio Participativo (participatory budget). In the same year, as part of the H2020 project Empatia, BiPart developed Empaville, a role playing game that simulates a participatory budgeting process. Building on the research undertaken in Empatia, Empaville is an experiment bringing together in-person deliberation techniques and digital technologies in the form of hybrid (offline and online) sessions. Since its inception in 2016, Empaville has been used in over 30 situations across Europe and North America.

In Empaville, participants play citizens of an imaginary island (Empaville), negotiating for 2-3 hours and seeking to come up with joint proposals for the area. At the start of the game, each participant is assigned a character card placed inside a badge. On the front, visible to all other players, is the character's name and his or her role in the game. On the back, hidden from the other participants, is information about his or her life, work, goals to be pursued and also his or her character that serves the participant to get into character and represent him or her during the game.

The fact that participants need to represent different characters that do not correspond to their social and demographic situation, therefore forcing players to practise empathy towards individuals and groups with needs and interests different than their own: “My character could be an elderly person, prejudiced against young people, so I would need to emphasise with this elderly person’s needs, putting myself in his or her shows, entering reality from a different perspective,” explained Stefano.

In the game, participants in groups of five sit at a table, interacting over a map of the city, divided into neighbourhoods, and a series of challenge cards laid out on each table. The challenges, indicated by these cards, are the issues, problems, and needs of the city of Empaville on which to reflect and co-design together with one's tablemates. With the help of canvas boards, participants are facilitated in the development of ideas and the articulation of the proposal presentation. In 30-40 minutes, participants must come up with one or two proposals together, trying to mediate between the parties and the interests of the whole table, as in a real deliberative assembly. Municipal experts present at the session can monitor the development of the proposals and assess their technical and economic feasibility according to the allocated budget and the object of the decision.

Once participants have developed a joint proposal for the area, they upload their proposal on the digital platform. The proposals are presented and discussed in plenary and finally put to a vote to decide which ones to implement with the available resources. During the voting phase, participants are invited to leave the tables and converse freely, to allow for further discussion and negotiation, typical of a pre-voting phase, and to access the BiPart platform both to vote on the proposals and, depending on the funds available to the citizens of Empaville, to crowdfund them.

In DARE, Empaville was adapted to Ravenna’s Darsena area: “We tried to collect all information about the context of the Darsena’s regeneration to transform our tools into something that can be useful to improve participation,” recalled Giulia. In this way the game included data and elements from the Darsena, making some aspects of the discussions realistic and applicable for the area.

However, despite the efforts to contextualise Empaville to the Darsena, the deployment of the game in DARE met a series of challenges, including the Covid-19 pandemic. “The pandemic actually challenged us a bit because we had to develop a completely new game without the 70% of the original activities developed in person,” remembered Stefano. “Empaville is about playing characters. Online, when there is no face to face interaction, you cannot play and behave like you are in an imaginary city, and you hardly have the whole picture, the shape of the characters in front of you.” In order to break the monotony of online calls, for the online implementation of Empaville BiPart relied on the platform gather.town that offered a map where people could cross the streets, meet in different rooms, sit in front of the table and discuss using an interactive blackboard.

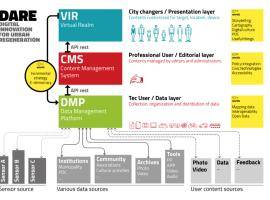

The Empaville sessions had a specific role in DARE’s project ecosystem. Instead of generating actual ideas for the Darsena, they were conceived as a form of ice breaking or training sessions for cooperation. However, BiPart’s e-democracy tools had various roles throughout the different phases of the project: “the idea is to involve people in different phases, to make proposals on the platform and keep following and discussing, trying to improve them,” explained Stefano. “People cannot meet regularly, so the platform needs to help increase the opportunities of participation and interaction.”

In the first phase (PROPOSE), initiatives for the Darsena area have been collected through a call by the municipality. Whoever intended to respond to this call had to publish their project ideas on the BiPart platform. By publishing their proposals, initiators could make their idea known and look for partners, building a partnership around this idea. This modality allowed many initiators to come into contact with other groups and transform their ideas based on these interactions. In the second phase (CONFRONT), proposals were matched with each other and broader tactics, developing synergies and inviting residents and other stakeholders to ask questions and make recommendations. In the third phase (DECIDE) citizens who registered with their ID and tax number could vote on the tactics they preferred: the tactic of the Green Darsena won with more than 800 votes over the visions of the Darsena Laboratory and Cosmopolitan Darsena.

Such an involvement of local residents and other actors through BiPart’s digital platforms was made possible by a variety of factors. On the one hand, the proposals mobilised local networks of citizens already involved in sports or leisure activities in the Darsena who also wanted to see their opportunities extended via the Green Darsena tactic. On the other hand, the digital environment and infrastructure created around the Darsena Ravenna Approdo Comune platform helped local citizens and initiators of projects in developing a familiarity of online tools, communication and cooperation. This familiarity was supported by a series of digital training sessions led by DARE consortium members and trained digital process facilitators. Furthermore, the complex architecture of DARE invited citizens to take a role in the project that went beyond traditional forms of participation. “Involving people in deliberating and discussing, rather than simply clicking and voting, is quite challenging,” reminded me Stefano. Afterall, real participation demands a continued engagement from citizens and responsibility in enforcing the collectively made decisions.