For the labour market, the scale of the Green Transition represents nothing less than an industrial revolution. Research shows that the most carbon-intensive sectors will disappear altogether, and that no industry sector will remain untouched. This shift will also create jobs and new businesses, although care is needed to ensure equal access to these. For example, only 32% of employees in the high-growth renewable energy sector are women. The International Labour Organisation (ILO, 2022) forecasts that without active policy intervention in such sectors, labour market disparities will continue.

Although quite optimistic about their ability to deliver a just transition in relation to the labour market, 70% of our surveyed cities identified specific groups at risk of being left behind. These included the low-skilled, those already in precarious employment, micro businesses and the self-employed.

What are cities’ capacity building priorities around jobs and skills for a climate neutral economy?

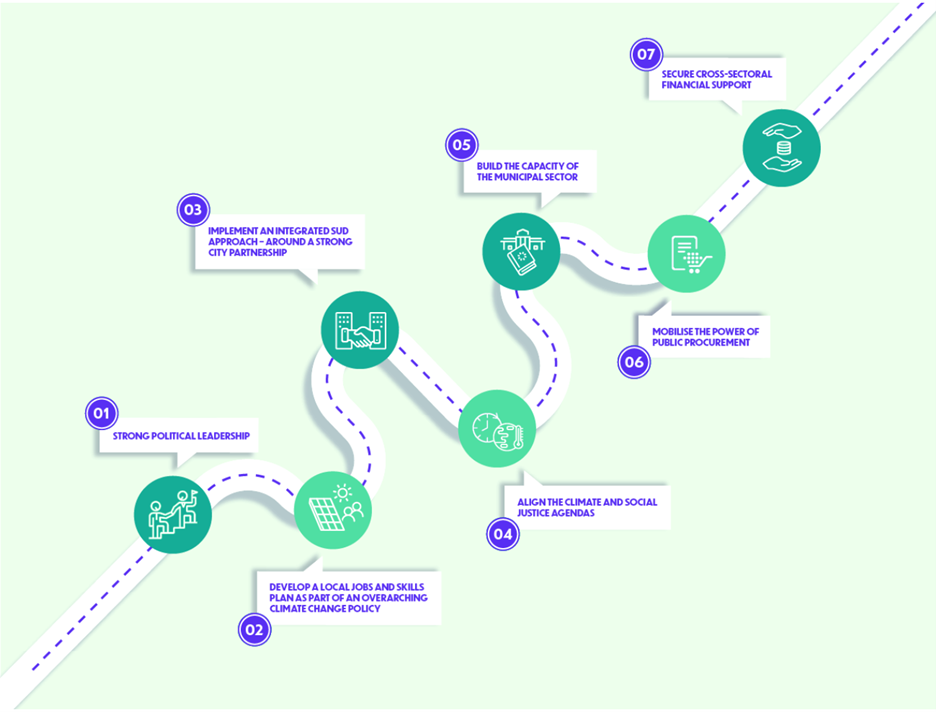

This review identifies the following five specific areas where it is critical to build the capacity of cities of all sizes.

1. Create a better understanding of future jobs and skills

In a fast-changing labour market being transformed by the megatrends of green and digital transition, providing reliable intelligence on the direction of travel is vital. Accurate skills forecasting is a key dimension to this. However, many cities struggle to identify future imbalances between labour supply and demand, as the process is complex and expensive, often requiring skillsets beyond the municipal sphere.

2. Understand how to bridge the gaps, anticipate changing demands, and redirect the skills pipeline

Urban economies rely on having the right skills mix in their population in order to function effectively. Cities with a booming economy create, attract and retain the right equilibrium of talent and skills. However, city authorities usually have limited competence in the education and skills field. Furthermore, redirecting the skills pipeline – often a regional or national competence – takes time. Meanwhile, the pace of the digital green transition is placing huge pressure on the skills system.

3. Building the capacity of the municipal sector

Low awareness levels and skills gaps within municipalities are routinely identified as major barriers affecting cities’ ability to respond effectively to the skills challenges created by the Green Transition. Cross-departmental working and external stakeholder collaboration are also key. However, small and medium sized cities in particular can find this difficult.

4. Strengthening the narrative to shift mindsets

The scale and speed of the industrial transition can be daunting. The complexity of the shift also makes it hard to explain in simple terms. Too often, the journey is framed entirely in negatives, and city authorities can struggle to present the opportunities and benefits to citizens.

5. Mobilising the right mix of resources

There is unanimity that public funds alone cannot support the transition to climate neutrality. This also applies to the question of green skills and the related new business chains that are emerging. Small and medium sized cities can lack the capacity to identify and secure the resources they need. This factor also inhibits their effectiveness in mixing funds from multiple sources.